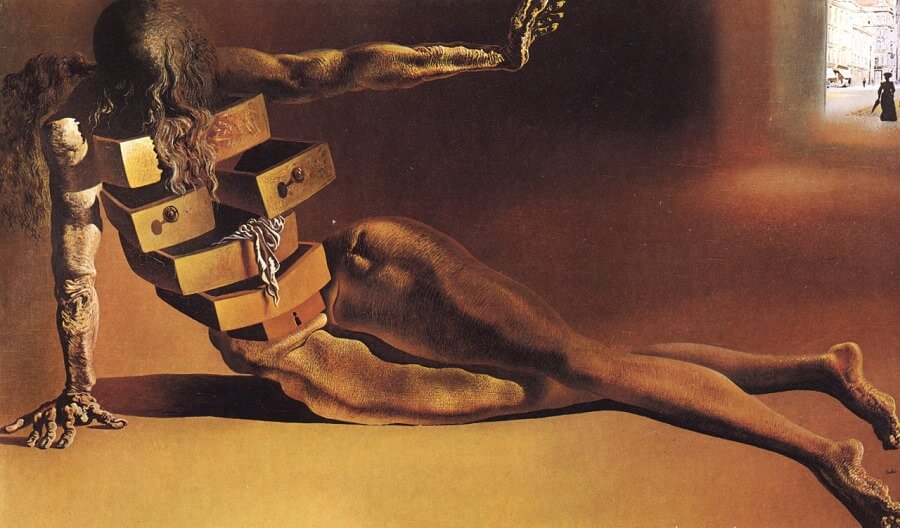

25 Feb The meaning of life according to Dali

Of the many films that were made about Dalí’s life and art, perhaps none captures his clownish personality paired with extraordinary artistry as effectively as Soft Self-Portrait of Salvador Dalí (1967). This “creative documentary” by director Jean-Christophe Averty and narrated in English by Orson Welles was shot on location at Dalí’s home in Port Lligat, Spain, and includes such arresting (and suitably “surrealistic”) scenes as Dalí ecstatically playing a piano filled with cats – a reconstruction of a ‘cat organ’ in which a line of cats is fixed in place with their tails stretched out underneath a keyboard so that the cats cry out in pain when a key is pressed. Dalí, it seems, also associated pianos with sexuality – a link formed in his childhood by a book of venereal diseases that his father left open on the family piano to teach his son the perils of promiscuity. Other episodes in the film are no less peculiar: The artist marching triumphantly across the Spanish landscape throwing fistfuls of feathers into the air with a plaster rhinoceros head in a wheelbarrow at two children dressed as cherubs in tow is a prime example, as is the moment in which he emerges from a giant egg, spraying milk, “symbolic blood”, and “symbolic fish” across the Mediterranean beach.

Welles describes Dalí as a “prince of paradox”, but amidst the humorous hijinks, Soft Self-Portrait proves to be one of the most informative documentaries on the artist’s life, detailing his emergence as an artist in the 1920s, his important contributions to Surrealism in the 1930s, and even his antecedence to 1960s Pop Art (Andy Warhol would later admit that he loved Dalí “because he’s so big”). The film is certainly not as well known as it should be, and the final sequence – an elaborate “happening” in which Dalí encloses himself in a clear plastic dome to “paint the sky” – confirms that Dalí was an extraordinary artist well beyond his heyday in the 1930s.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.