09 Feb ARD 517-What exactly is still life? that is, a bit of history and terminology.

Still life is a painting genre that includes compositions, usually paintings or drawings, consisting of relatively small, stationary, most often inanimate objects, selected for compositional and aesthetic or symbolic reasons.

Still life is nothing more than a moment from everyday life that has been stopped for a while. Maybe it, among others. be a bouquet of flowers, a bowl of fresh fruit, a plate of oysters, which are a manifestation of beauty and wealth. When analyzing a still life, we must take into account its universal dimension. This type of art is fashionable and desirable because it tries to satisfy, above all, the need for beauty.

Still life is a kind of mainly artificially created composition, in order to present it as effectively as possible, consisting of all kinds of everyday objects – kitchen and tableware, furniture, fabrics, as well as flowers or hunted animals, weapons, foodstuffs. Basically, objects are arranged in such a way that they create the most sophisticated color combinations and light games.

Common elements of still lifes are fruit, flowers, books, dishes, weapons, hunting tools, kitchen utensils, smoking utensils, candles, cards, and other games, musical instruments, etc., fish, bread, eggs, etc., sometimes arranged in a composition intended to suggest a ready meal, e.g. breakfast. Small live animals such as insects and crustaceans also appear in still lifes. If a larger animal or – sporadically – even a human figure appears in the still life, then never as the main topic. The human skull is a frequent and important motif for symbolic reasons – associated with the thought of the passing and vanity of life and temporal goods (Vanitas), often included in the works of this genre. Within the still life, there may also be works of representational arts, such as sculptures and paintings, which in turn depict human figures.

Around 1650, the term stil-leven (literally “quiet, motionless life” in the sense of “stationary model”) appeared in the Dutch art inventory to denote a still life image. In the early In 18th century, the term was used by the Dutch art historiographer Arnold Houbraken. The Dutch language later developed, among others, German stilleben and English still life.

The first still lifes appeared in ancient art. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, they often accompanied figural scenes and, as a rule, had a symbolic meaning. In the 15th century, in the Netherlands and in Italy, there were attempts to make the still life independent in miniatures or on the wings of small polyptychs.

The first still life treated as an independent subject was painted in 1504 by Jacopo de ‘Barbari.

In the 16th century, still lifes were also created by Caravaggio,

Pieter Aersten,

and Joachim Beuckelaer.

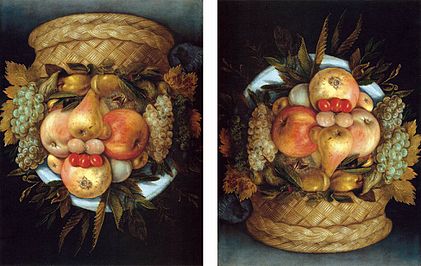

The mannerist Giuseppe Arcimboldo created fantastic figures composed of flowers and fruit.

It developed as a separate genre in the 17th century, mainly in Dutch and Flemish painting. It quickly became very popular all over Europe.

Pictures of still lifes are known from antiquity, mainly from wall decorations and floor mosaics created in the Hellenistic period in Greece and Rome. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the dominant Christian art for many centuries dimmed this secular in nature motif, which, although it appeared regularly in medieval and Renaissance art, was only a fragment of a larger figural scene and usually had a symbolic meaning.

As an independent subject, still life first appeared in the 16th century in Italy in the art of Jacopo de Barbari, and became independent at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries in the Netherlands, where the prevailing Protestantism strongly influenced the disappearance of religious painting. This enabled the development of landscape, portrait, and genre art, including still life, which very quickly became popular throughout Western Europe.

It is worth noting that initially, this species retained its symbolic meaning. The vanitas (Latin vanity) motif is very popular in this context, reminding us of the fragility and volatility of human life with the help of symbolic objects such as a skull, soap bubbles, hourglass, cut flowers, extinguished world or empty, sometimes overturned dishes.

in the 17th century, more and more works emerged from the observation of “quiet life” and depicting simply common frames from everyday life, which allowed to emphasize the charms of objects included in the painterly compositions. Great thematic diversity allows distinguishing numerous types of still lifes.

Still life can be divided into several different categories depending on what themes are about. Below the most popular types of still life along with its most prominent representatives.

Floral

The images primarily focus on the presentation of bouquets. You can see them in vases or lying flat on the surface.

Representatives: Willem van Aelst, Ambrosius Bosschaert, Jan Brueghel (the elder), Rachel Ruysch.

Fruit

Various types of fruit can be seen in the images, including but not limited to apples, pears, cherries, grapes. The fruit can also be arranged in a bowl or basket.

Representatives: Ambrogio Figino, Luis Meléndez, Louise Moillon.

Breakfast (banquet)

This is a category of still life that mainly presents food products. These include, but are not limited to, bread, eggs, butter, cold cuts, fruit, dishes, e.g. cups, jugs.

Representatives: Osias Beert, Floris van Dijck, Georg Flegel, Willem Claesz Heda, Clara Peeters, Floris van Schooten.

Musical

Various types of musical instruments can be seen in the paintings. The most popular is the violin.

Representatives: Evaristo Baschenis, Bartolomeo Bettera.

Animal

Images in this category primarily present various types of animals – most often after hunting, which is why this category is also called hunting.

Representatives: Jan Fyt, Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Frans Snyders

Market and kitchen

In the paintings you can see a still life characteristic of kitchens, stalls and pantries. These are mainly various types of food products, including fruit, vegetables, preserves, meat, eggs, drinks stored in jugs.

Representatives: Pieter Aersten, Joachim Beuckelaer, Vincenzo Campi, Adriaen van Utrecht.

Vanitas (vanitas)

It is a category of symbolic still life that takes up the topic of vanitas, or vanity. It is a motif related to learning, sometimes passing death, very popular in the Middle Ages and the Baroque period.

The subject of vanitas was very often undertaken by still life painters from Flanders and the Netherlands. You can see many symbols in the paintings, for example skulls, hourglasses, clocks, wilting or rotten fruit.

The vanitas motif in the play is to make the viewers aware that life is a passing moment, that each of us is mortal.

Representatives: Sebastien Bonnecroy, Pieter Claesz, Evert Collier, Cornelis Gijsbrechts, Jacques Linard, Simon Luttichuys, Antonio de Pereda, Simon Renard de Saint-André, Harmen Steenwijck, Jan Vermeulen.

Kunstkamera

Kunstkamera (from German Kunstkammer, Kunst, meaning “art” and Kammer, “izba”, also a panopticon), or a cabinet of curiosities. It is a term for a collection of items that can also be captured in a painting.

Representatives: Frans Francken the Younger, Willem van Haecht, Georg Hainz, Jan van Kessel.

Trompe l’oeil

This term refers to illusionist painting. The paintings present illusionistic representations that give an illusion of reality, for example, they try to show three dimensions on a two-dimensional surface.

This painting was especially popular in the Netherlands, Italy and Spain. It presents small objects that seem real thanks to the appropriate play of light and shadow.

Illusionist painting was also very popular in the United States at the turn of the 20th century – its outstanding representatives were William Harnett, John Haberle, Levi Wells Prentice and John Frederick Peto.

Representatives: Samuel van Hoogstraten, Domenico Remps, Cornelis Gijsbrechts, Evert Collier.

Allegory of the five senses

Images allegorically present human senses.

Representatives: Gererd de Lairesse, Giuseppe Recco, Sebastian Stoskopff.

Bibliography

Battistini M., Impelluso L., Zuffi S., Still life. History, masterpieces, interpretations, K. Wanago (trans.), Warsaw: Arkady, 2000, ISBN 83-213-4194-2, OCLC 749373546.

Charles Sterling, Still Life from Antiquity to the 20th Century, Warsaw: Wyd. Science. PWN; WAiF, 1998. ISBN 83-01-12468-7.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.